Historically, membership in a Quaker meeting was traditionally established in one of three ways: birth, transfer, or request.

According to the 1819 edition of the Discipline of the Society of Friends of Ohio Yearly Meeting, any child “whose parents have accomplished their marriage according to our Discipline” would automatically be considered a member. These individuals were referred to as birthright Quakers. Even if one parent was disowned (that is, if the parent’s membership in the meeting was revoked) before the child was born, that child would still be considered a birthright member.

An individual could also transfer membership from one meeting to another. Like many other Americans during this period, Quakers were moving around the country with considerable frequency. Nevertheless, the Discipline discouraged relocations, “especially where the inclination to such removals hath originated in worldly motives.” In other words, the advantages of maintaining a stable community should be weighed against the monetary gains that might come with a change of residence.

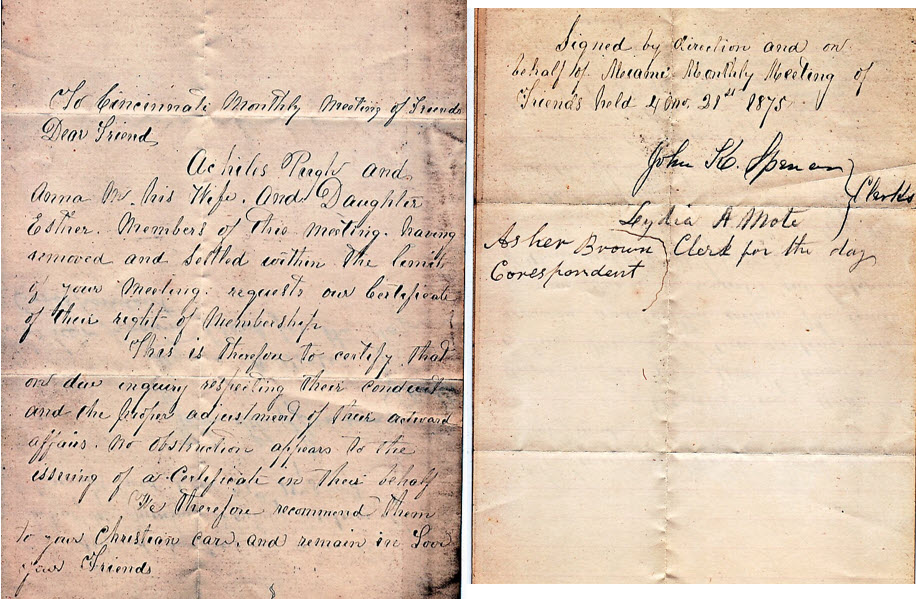

When relocations did occur, the original meeting would grant a certificate to the individual, indicating that the person was a member in good standing and that there were no obstacles to the move (such as unpaid debts). That certificate would be presented to the new meeting, and was typically accepted without question. (Many of the first members of Cincinnati Monthly Meeting had originally transferred their membership from other parts of the country to Miami Monthly Meeting. Since Cincinnati Monthly Meeting was initially subordinate to Miami Monthly Meeting, there was no need to formally transfer those memberships; those individuals were considered charter members when Cincinnati Monthly Meeting was established in 1815.)

The first directory of the meeting, which was compiled in 1819, listed about 180 members. Between 1815 and 1827, Cincinnati Monthly Meeting received almost 340 men, women, and children from other meetings. About 60% were from the East—predominantly Pennsylvania, New York, Virginia, New Jersey, and Maryland. But many also came from north of town, particularly Miami Monthly Meeting in Warren County, Center Monthly Meeting in Clinton County, and Short Creek Monthly Meeting in Jefferson County (in west-central Ohio, where Ohio Yearly Meeting met). Eleven even came directly from England, Ireland, and Wales.

For some, Cincinnati was just a stopover. The six children of Jeremiah Wilson Sr. were received from Darby Creek Monthly Meeting in February of 1819, and were promptly granted a certificate to move to Lick Creek Monthly Meeting in Indiana the following month. For others, the stay lasted a little longer. William and Catharine Tilton and their three children were received from New York Monthly Meeting in the fall of 1817, but when William died in the summer of 1819, Catharine decided to take the children back home to New York.

Indeed, during this period, Cincinnati Monthly Meeting granted more than 200 certificates to members who wanted to relocate elsewhere, with about half of those pushing further west into Indiana, particularly to Silver Creek, White Water, and West Grove Monthly Meetings. And while many Quakers were making their way from the rural areas into town, many were also going back to the country. Almost the same number of individuals transferred to Miami Monthly Meeting as came from there to Cincinnati, with a small number going to Clear Creek Monthly Meeting and elsewhere in Ohio. Only a handful retreated back East.

Those who were not birthright Quakers or did not transfer their membership from another meeting had to submit a request for membership. During the early years, such a request from a “convinced Friend” would have been made to the overseers, who would then bring it before the men’s or women’s business meeting (depending on the gender of the applicant). Several members would then visit the potential member and, as suggested in the Discipline, “inquire into the lives and conversation of the applicants, and also to take solid opportunities of conference with them, in order the better to understand whether their motives for such requests be sincere, and on the ground of convincement...the neglect of such caution having often been injurious both to the individuals and to Society: to them, by settling them in a false rest; and to Society, by adding to its numbers without increasing its joy.”

Cincinnati Monthly Meeting conscientiously observed those instructions. In one instance, the Friends “appointed in the case of David Longacre report they had an opportunity with him and thought him a well meaning young man, but did not believe him to be sufficiently convinced of Friends principles.” To ensure that his application was given thorough consideration, Elias Fisher was asked to join the committee and report back at a future date. These discussions continued for nine months, until the monthly meeting finally noted, “The committee in the case of David Longacre report they attended to their appointment, and agreed to propose that his case be discontinued from the minutes, which is concurred with.” Longacre was one of very few who was never accepted as a member.

This article comes from the book Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to Cincinnati Friends Meeting.

Interesting article, Sabrina! Thank you!!

I love it that the goal of additional members is “increasing its joy.” That resonates deeply with me.