Since its beginnings in the 17th century, the Religious Society of Friends had dispensed with an official priesthood. This raised an important question within the community: how were marriages to be conducted? Our Society's founder, George Fox, prescribed an orderly process:

I was moved to exhort them to bring all their marriages to the men’s and women’s [business] meetings, that they might lay them before the faithful; so that care might be taken to prevent those disorders that had been committed by some. For many had gone together in marriage contrary to their relations’ minds; and some young, raw people that came amongst us had mixed with the world. Widows had married without making provision for their children by their former husbands, before their second marriage.

When Cincinnati Friends Meeting was established in 1815, it continued to follow these guidelines. The Discipline of 1819 that guided Quaker faith and practice at that time recommended that unmarried people should “seriously and humbly wait upon the Lord for his counsel and direction in this important concern; and when favored with satisfactory clearness therein, they should early acquaint their parents or guardians with their intentions, and wait for their consent.” With the consent of their parents in hand, the next step was for the couple to inform the meeting in writing. Two male and two female Friends would then be appointed to investigate the couple and ensure that there were no obstructions, such as an existing engagement.

Marrying within one year of a spouse’s death was discouraged, as were marriages between first cousins or with “those who are not in membership with us.” Friends were also admonished to guard against “improper or unequal connections in marriage; that they be not anxious to obtain for them large portions and settlements; but that they be joined to persons of religious inclinations, suitable dispositions, and diligence in their business—which are necessary to a comfortable life in a married state.”

If the individuals intending to marry were not part of the same meeting, the man had to obtain a certificate from his meeting, testifying to his membership in the Society and freedom from any obstructions, as well as written consent from his parents or guardians, if appropriate. He then had to present that to his future bride’s meeting and obtain its consent.

If the meeting agreed to “leave them at liberty to accomplish their marriage,” the couple could then make arrangements to have the ceremony during the usual weekday meeting for worship. Alternatively, they could request a special meeting for the occasion “at a seasonable hour in the forenoon on some other convenient week-day, and at the meeting house to which the woman belongs.”

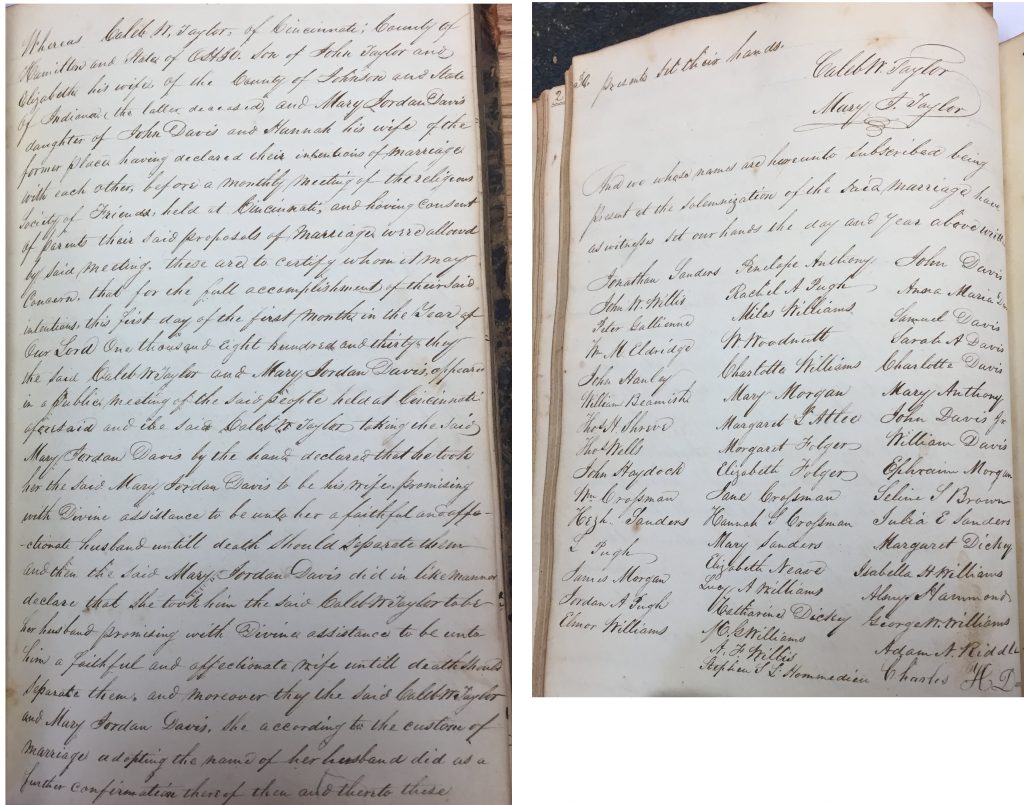

After a period of silent worship, the couple would stand, take each other’s hand, and promise, with divine assistance, to be a loving and faithful spouse. (Unlike wedding ceremonies in other denominations, where women had to promise to obey their husbands, Quaker vows were the same for both genders.) The marriage certificate as prescribed in the Discipline would be read aloud, signed by the couple, and then signed by their relatives and witnesses to the ceremony.

Two Friends of each gender who were appointed by the meeting to attend the wedding were expected to “take such aside who make any breach upon good order, and in an affectionate manner admonish them to a better behavior; and the said overseers are to make report to the monthly meeting, whether good order has been observed, and take care that the marriage certificate be returned in order to be recorded.” Between 1815 and 1827, eleven marriages were recorded by Cincinnati Monthly Meeting.

Although good order was typically followed, the lack of sufficient decorum at some weddings prompted a discussion at a monthly meeting in 1820. Cincinnati Friends agreed that it was necessary to “discourage any young men going into the women’s appartment” (that is, the women’s side of the meetinghouse). In addition, after the marriage certificate was read, “the meeting [was] to resume its former stillness and conclude as usual, none of the parties to disperse before the conclusion of the meeting.”

As in all things, Quakers encouraged simplicity in their wedding ceremonies. “Friends in affluent circumstances, particularly, may be careful to set a becoming and encouraging example of moderation—avoiding unnecessarily expensive entertainments, and large companies,” recommended the Discipline. After the ceremony, the members of the wedding party were expected to avoid “intemperate or immoderate feasting or drinking” and to “retire to their home in seasonable time.”

This article comes from the book Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to Cincinnati Friends Meeting.

In addition, to see a video about some of our more contemporary weddings, see Quaker Weddings on YouTube.