Marriage in the Manner of Friends

Last August, I gave a brief presentation on Quaker weddings at the annual interdenominational Festival of Faiths. This presentation included a six-minute video that featured the photos, memories, and perspectives of some of our members who had married in the manner of Friends (You can view the video by clicking here.)

Last August, I gave a brief presentation on Quaker weddings at the annual interdenominational Festival of Faiths. This presentation included a six-minute video that featured the photos, memories, and perspectives of some of our members who had married in the manner of Friends (You can view the video by clicking here.)

Putting together this video was an interesting experience for me. My own first exposure to Quaker wedding traditions came when I was researching the history of Cincinnati Friends Meeting for our 200th anniversary—reading nineteenth-century minute books and old editions of The Discipline, a publication containing guidelines and advice from the yearly meeting to its constituent monthly meetings. (We now call this document Faith and Practice.)

Although the underlying principles behind our wedding traditions—simplicity, equality, and community—have remained the same, several practices have changed over the past 200 years. So let’s take a step back in time and take a look at how Friends used to approach weddings.

Imagine, if you will, that the year is 1838. You’re a young Quaker man, ready to settle down. The possibilities for a partner are endless, right?

Not so fast!

Whom may you not wed?

The first rule for any Quaker considering marriage was this: You cannot marry a non-Quaker. Of course, this type of restriction was not unique to Friends. Many religious traditions discouraged inter-faith marriage, and the Quaker objection to it was the same as that of other denominations: concern for marital conflict over differing spiritual views and practices, especially with regard to rearing children.

Another rule was related to relatives: You cannot marry a first cousin. For Cincinnati Friends, this was not a huge problem. Our meeting was on the frontier during a national westward migration, and we were drawing members from all across the country. So it was much easier for a young Quaker in Cincinnati to meet someone who was not a close relative.

For meetings in farming communities that had existed for generations, this was more of a problem. Quakers tended to have large families. If your father was one of five children, and your mother was one of five children, and each of their siblings had five children, there were 50 people in your meeting who were off the table! One of the ways young people compensated for this was to attend the annual sessions of the yearly meeting, which drew attendees from multiple counties or even multiple states. Yes, young Friends came to hear the committee reports and to discuss such things as whether Quakers should work with Methodists on abolition. But there was also a lot of wooing going on, lots of clandestine buggy rides!

Another rule regarded widows and widowers. Individuals who lost a spouse were discouraged from marrying within a year of their spouse’s death. It must have been a hardship—a man suddenly finds himself with many young children and no means of taking care of their daily needs, a woman suddenly find herself with many young children and no means of taking care of their financial needs. But I think part of the reason for this restriction was to give the person an opportunity to grieve, and to avoid rushing into marriage for pragmatic reasons rather than taking the time to forge a genuine bond with a new partner.

So—you’ve met a nice Quaker girl who’s not your cousin and not recently widowed. All you have to do is pop the question and plan the wedding, right?

Not so fast!

Who must approve?

As in so many things, Friends had an approval process when it came to marriage. And the first approval that Quakers needed was from God. Here’s what The Discipline had to say:

It is affectionately desired by the Yearly Meeting, that all young or unmarried persons in membership with us, previously to their making any procedure in order to marriage, do seriously and humbly wait upon the Lord for his counsel and direction in this important concern.

Quakers considered marriage not just a matter of attraction or compatibility, but also as a spiritual issue that required discernment. Each individual’s heart had to be clear.

The next level of approval came from the parents. It’s worth noting that the prospective groom did not go to the prospective bride’s father to ask for her hand. Quakers did not consider women to be possessions to be passed from one man to another. The young man would ask his parents; the young woman would ask hers.

Of course, the parents of any young person would certainly have been aware of their child’s courtship, and The Discipline encouraged parents to lend a guiding hand:

It is further recommended that parents exercise a religious care in watching over their children, and endeavor to guard them against improper or unequal connections in marriage; that they be not anxious to obtain for them large portions and settlements; but that they be joined with persons of religious inclinations, suitable dispositions, and diligence in their business—which are necessary to a comfortable life in a married state.

However, the parents did not necessarily have the final say in the approval process. They weren’t allowed to object for arbitrary reasons—for example, if the young lady was a bad cook, or if the young man made a funny noise when he laughed. Ultimately, in the face of parental objections, the couple could take their concern to the Monthly Meeting for the final determination about whether they could proceed.

Another level of approval had to come from the master or mistress of an indentured servant or apprentice. For example, a young Quaker lass in Ireland might want to come to the United States, but couldn’t afford it. A Quaker family here in Cincinnati might pay her travel expenses and give her free room and board in exchange for her working for them as a servant for a few years. Likewise, a young lad might become an apprentice to a skilled craftsman who would teach him the trade in exchange for his working for him for a given period of time. If that young woman then met someone and wanted to go off to start her own household, or if that young man wanted to leave town to marry someone who lived elsewhere, they’d have to get permission to do so. Keeping your word with regard to contractual agreements was a matter of integrity. Sometimes the master or mistress might release the young person from their commitment, sometimes not.

The final approval had to come from the couple’s Quaker meeting. About two months before the wedding was to take place, the couple had to announce their intention to marry at Monthly Meeting. The clerk would then appoint two men Friends and two women Friends to make sure there were no obstructions to the marriage, such as one party having made a previous commitment to another person during one of those clandestine buggy rides at yearly meeting.

In the case of a widow, the meeting also made inquiries to ensure that the legal rights of her children from her previous marriage had been secured so that the youngsters could not be disinherited or cast aside.

At the next Monthly Meeting, the committee would give their report. If there were no obstructions, and the couple reaffirmed their intention to marry, then they were set at liberty to wed. Now it was just a matter of picking the time and place, right?

Not so fast!

Where, when, and how?

If the prospective bride and groom were both members of the same meeting, the wedding would take place at their meetinghouse. If they were from different meetings, then the wedding would take place at the bride’s meetinghouse. The groom had to get a certificate of clearness from his own meeting, allowing him to travel to another location to accomplish the marriage.

The wedding itself would take place during meeting for worship; it was not a separate event. Most nineteenth-century Quaker meetings held worship on both Sunday and a mid-week morning. Here in Cincinnati, that was on Thursdays. If for some reason the couple could not get married on a Thursday morning, the Monthly Meeting could authorize a special meeting for worship on another weekday.

In addition, a committee of four Friends was appointed to attend the event to make sure that “good order” was followed.

What is “good order” for a wedding?

One aspect of good order at a Quaker wedding was that the bride and groom would enter the worship room together. They were considered equal partners; the bride was not “given away” to the groom because she was not considered her father’s property. The couple were giving themselves to each other.

Another aspect of good order was that there would be no officiant. Cincinnati Friends have had ministers since the meeting was founded in 1815, sometimes two or three at a time. Those individuals and possibly others would likely give vocal ministry on such a special occasion. But they played no role in the ceremony itself.

After a period of silent worship, the bride and groom would rise and take each other by the right hand. They would then say their vows to each other, which were identical except for their names and roles. The groom would say these words:

Friends, in the presence of the Lord, and before this assembly, I take this my friend Hannah Davis Taylor to be my wife; promising, with divine assistance, to be unto her a loving and faithful husband, until death shall separate us.

The bride would say these:

Friends, in the presence of the Lord, and before this assembly, I take this my friend Murray Shipley to be my husband; promising, with divine assistance, to be unto him a loving and faithful wife, until death shall separate us.

Then they would resume their seats, and worship would continue.

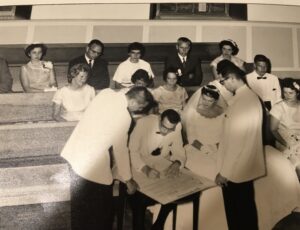

Toward the end of worship, an individual would rise and read aloud the marriage certificate. This tradition began in the seventeenth century, when the Religious Society of Friends was founded. At that time in England, the church and state were one entity, and only weddings officiated by a minister of the state church were considered legal. Friends whose weddings were not presided over in such a way needed another way to prove that an official union had taken place. The marriage certificate was intended to be such a document. It included the names of the bride and groom, the names of their parents, where they resided, where and when the wedding had taken place, and what their vows to each other were. This document was placed on a table, and the bride and groom would both sign it, with the bride using the groom’s last name. Then other members of the family signed, as did all who were present. The certificate would later be copied into the records of their Monthly Meeting, and couple kept the certificate itself as evidence of their marriage, should it ever be questioned.

Quakers expected good order to be followed not only during the wedding ceremony itself, but also afterwards. At any post-nuptial celebration, Friends were still expected to follow the rules of decorum: no intemperate or immoderate feasting or drinking, no wanton or unseemly behavior, no carrying on into the night, and no expensive entertainment.

What if good order was not followed?

The consequences for failing to follow good order depended on the nature of the offense. For a minor infraction, such as ducking out of worship early to get to the party, The Discipline encouraged any concerned Friend to take the person aside and, in an affectionate manner, admonish them to better behavior.

For a major violation, such as marrying a non-Quaker or having the wedding performed at a courthouse or by an ordained member of another denomination, the result could be disownment.

Disownment among Friends was not equivalent to excommunication or shunning. It had no implication regarding the person’s spiritual state, and Quakers who were disowned could still be friends with Friends and sometimes even still came to worship. However, they could not serve in any official capacity or participate in the meeting’s decision-making process. And they could not call themselves Quakers.

To avoid this, a person could admit before the Monthly Meeting that they were wrong in breaching good order and regretted their action. But that was rare; most Quakers relinquished their membership rather than doing so.

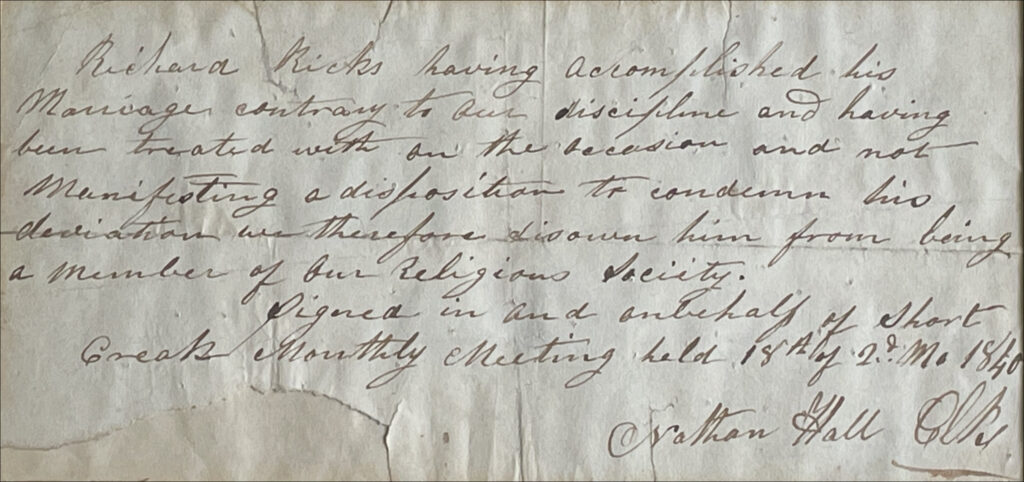

Such was the fate of one of our current minister’s ancestors, who received the following certificate of disownment:

Richard Ricks, having accomplished his marriage contrary to our discipline, and having been treated with on the occasion, and not manifesting a disposition to condemn his deviation, we therefore disown him from being a member of our Religious Society.

What has changed over time?

The nineteenth century was a period of tremendous change for the Religious Society of Friends on many fronts, and one of them was in their attitude toward inter-faith marriage. By far the largest reason for losing members was due to disownments for marrying non-Quakers. In addition, it had become clear that even those who did acknowledge their failure to follow the rules were doing so in a perfunctory manner, compromising their own integrity. By 1864, marrying a non-Quaker was no longer a disownable offence.

Over the past two hundred years, other practices have evolved as well. When a Meeting appoints a clearness committee for an engaged couple, their focus is not to make sure there are no obstructions to the marriage, but rather to give the individuals an opportunity to reflect on whether they’re fully prepared for marriage. For example, what areas of difficulties do they foresee? Have they talked about their attitudes toward money and parenting?

Many Friends have also adopted some contemporary customs. I can’t imagine anyone getting married on a Thursday morning! In the latter part of the nineteenth century, many meetings introduced music into worship, and nowadays it’s not uncommon for Quakers to incorporate music into their weddings, especially when they have an acquaintance with musical gifts. Flowers and more formal attire became more commonplace. Some couples see the practice of “giving away the bride” as a tender way for a family member or friend to participate in a special moment.

Cincinnati Friends Meeting is an open an affirming Meeting, and the traditional wedding vows were not designed for same-sex marriage. Some couples, regardless of gender, choose to say vows that express their personal sentiments rather than using the old wording. Many also choose to exchange rings during their ceremony, although that was not the custom of early Friends.

Many couples do still find it meaningful to have their family and friends sign their marriage certificate. These documents often incorporate beautiful calligraphy and artistry, although they might not include the level of genealogical detail that the historic certificates contained.

Yet regardless of the exact nature of the preparation or the wedding itself, Friends continue to view marriage as a spiritual union, blessed by God and surrounded by love.

I really enjoyed the live presentation, which closely matches this. Thanks for your careful research and thoughtfulness.

Thanks, Cathy! I enjoyed giving it!

Really good article, Sabrina! Informative and fun to read.

Glad you enjoyed it! Sorry the recording didn’t turn out as well as we had hoped!

This was good, Sabrina. Thank you for sharing!

– Brian Page

Thanks! Did you get a chance to watch the video? Some familiar faces there! 😊

What a wonderful research and writing. Thank you Sabrina.

Thanks, Bill! Did you get a chance to see the video? Some familiar faces there! 😊