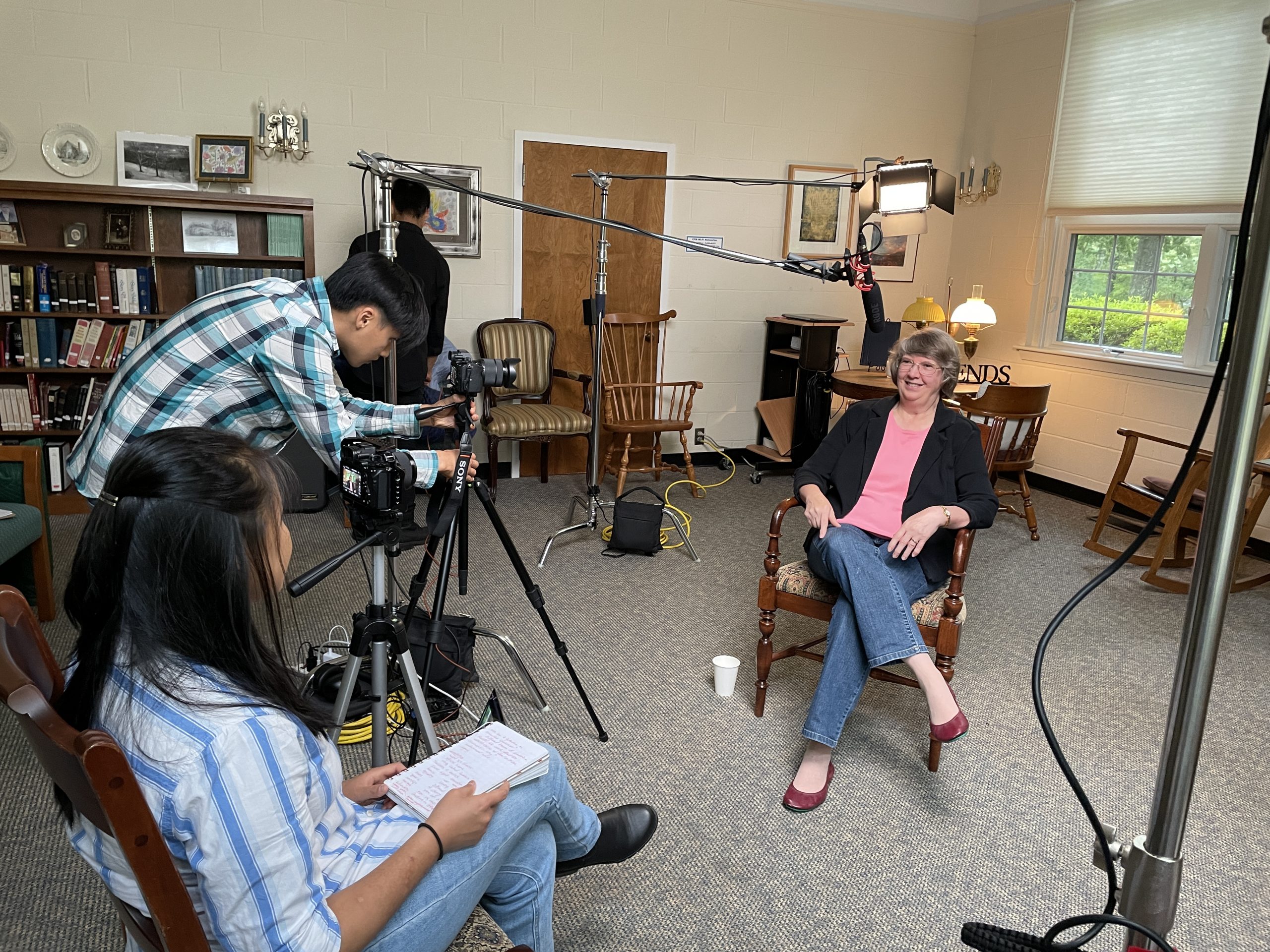

While being interviewed recently for a documentary on Agents of the Underground Railroad, I was asked about the relationship between the abolitionist Levi Coffin and the other members of Cincinnati Friends Meeting. And the answer was . . . it’s complicated.

By the nineteenth century, all yearly meetings in North America had a testimony against slavery. However, being anti-slavery and being an abolitionist were not the same thing. Some Friends favored the idea of persuading individual slave holders to gradually manumit their slaves. Some believed in colonization: since slaves in North America were originally taken from Africa, the way to right this wrong was to send them back to Africa. (The republic of Liberia was created specifically for this purpose.) For the abolitionists, however, slavery was inherently evil, and the only acceptable response was the immediate emancipation of all slaves so that they could live out their lives in freedom here in the United States. Many Quaker abolitionists were willing to work with other religious or political groups that shared their convictions, which made some Friends a little uneasy. A number of those groups were willing to go to war over the issue—a position that many Friends were unable to take. Opposed as they were to slavery, they were equally opposed to war.

By 1842, the tension between the more moderate factions and the abolitionists caused a split in Indiana Yearly Meeting, the larger Quaker organization to which Cincinnati Friends Meeting then belonged. The moderate faction retained the name Indiana Yearly Meeting; the abolitionist faction became known as Indiana Yearly Meeting of Anti-Slavery Friends. One of the instigators of the split was Levi Coffin, who was then living in Newport, Indiana.

While in Indiana, Levi was extremely active in the Underground Railroad—a network of both white and black individuals who helped runaway slaves escape to freedom in the Northern states and Canada. Levi also tried to undermine the economic foundation of slavery by operating a mercantile business that carried no products produced by slave labor. It was his experience in this work that prompted the Free Produce Association to ask Levi to move to Cincinnati to open a wholesale repository of free labor goods. Because of its location on the Ohio River, Cincinnati was a huge center of commerce west of the Alleghenies. In the spring of 1847, Levi and his wife Catherine and two children made the move.

Given his role in the schism of Indiana Yearly Meeting, and the fact that Cincinnati Friends Meeting remained affiliated with the more moderate faction, Levi was viewed as a somewhat controversial figure here in Cincinnati. His children weren’t admitted into membership until 1855, after the reunion of Indiana Yearly Meeting and Indiana Yearly Meeting of Anti-Slavery Friends. When Levi himself applied for membership in 1858—more than ten years after his arrival in town—the committee appointed to visit with him was “united in judgment that the present is not a proper time to accede to his request.”

In 1862, when the Contrabands’ Relief Commission of Cincinnati was formed, Levi was eager to help in its work of providing aid to the thousands of fugitive slaves (referred to as contrabands) who were flocking toward the advancing Union troops in the Mississippi River valley. However, the idea of accepting him into that organization provoked debate among its members. Levi sometimes displayed a confrontational attitude, and the members of the Commission were concerned that embracing him might actually make the public less likely to support their cause. Although they did ultimately allow him to join their group, a disagreement about the focus of their efforts—whether it should concentrate strictly on urgent aid such as clothing, or on both urgent aid and education—prompted Levi to leave the Commission and instead become part of the Western Freedmen’s Aid Society. (Not long afterwards, both groups ended up providing both urgent aid and education.)

One Friend writing from Spiceland, Indiana, to the president of the Contrabands’ Relief Commission (who was a member of Cincinnati Friends Meeting) expressed consternation that Levi made disparaging remarks about his fellow Quakers:

[Levi Coffin] said [the Contrabands’ Relief Commisssion] was made up of Hicksites and Infidels. Now seriously, is it right that Friends of your Monthly Meeting should allow one of its members to charge under any circumstances A. M. Taylor, James Taylor, Murray Shipley, and others (for he knows you are not Hicksites) with being Infidels? More especially, should he be allowed to do so while travelling under pay as the agent of an association engaged in the same work you are?

I am truly sorry he acts as he does, and fear it will have a bad effect for the cause of the sufferers. Already I hear of those who are unwilling to contribute . . . and I am sure I don’t want to pay anything to hire Levi Coffin to denounce your Commission . . . still less to call my fellow [Christians] Infidels.

George Evans to A. M. Taylor, letter, March 26, 1863, Taylor Family Papers, Quaker and Special Collections, Haverford College.

After the Civil War ended in 1865 and slavery had been abolished, Levi enjoyed a more amicable relationship with Cincinnati Friends Meeting. He was received into membership in 1866, and in 1871 he was appointed an Elder—an individual responsible for attending to the spiritual well-being of the meeting.

By the time Levi died in 1877, he had become a very popular figure in town. When his memorial service was held at the Eighth Street meetinghouse, the building could not accommodate everyone who wanted to attend, and hundreds had to remain outside. Four of his eight pallbearers were black men who had worked with him on the Underground Railroad.

Shortly after Levi’s death, members of the black community in Cincinnati held fundraisers for a memorial for him, but no action appeared to have been taken at that time. However, in 1901, they approached Cincinnati Friends Meeting about erecting a monument to Levi in our section of Spring Grove Cemetery. Although Quakers prefer small, simple markers without any epitaph, the meeting acceded to this request. The six-foot marker honoring both Levi and Catherine was unveiled on May 30, 1902, including the following inscription:

Levi Coffin

Died 9th Mo. 16, 1877

In His 79th Year

A Christian

Philanthropist

Catherine Coffin

Died 5th Mo. 22, 1881

In Her 78th Year

Her Work Well Done

Noble Benefactors

Aiding Thousands

To Gain Freedom

A Tribute From

The Colored People

Of Cincinnati

Clearly, Levi was a complex figure: a prophetic voice who spoke out boldly against slavery, a challenging personality who provoked divisions among Friends, and ultimately a man revered for his work in aiding more than 3,000 slaves escape to freedom via the Underground Railroad. His legacy shines on through the lives of the descendants of those whose liberty he helped to secure.

“Hicksites and infidels.” Wow. Wouldn’t we like to know more about the context of that statement, to hear his “tone of voice”? Taken at face value, it seems divisive and incendiary. Does he mean infidel Quakers or infidel Christians? I’m glad to hear that over time these divisions were healed and he was integrated into the life of the Meeting.

I’m struggling to imagine a tone of voice in which calling someone an infidel would be warm and humble. 🙂

The general context is that agents of both the Contrabands’ Relief Commission and the Western Freedmen’s Aid Society were going to various Quaker meetings, trying to encourage donations to their particular organizations. The Contrabands’ Relief Commission did in fact include at least one Hicksite, Jason Evans. I always considered that a tribute to the willingness of the Orthodox on the Commission to work “across the aisle,” given that there was still a great deal of animosity between the two factions.

Of the twelve members of the Commission, nine were Orthodox Friends. Is it possible that the other two (besides Jason, the Hicksite) were not affiliated with any religious organization, and therefore “infidels”? Maybe. But I think it would be an exaggeration to say that the Commission was “made up of” Hicksites and infidels, given the large presence of Orthodox Friends.

The letter writer suggests that Levi was being paid by the Western Freedmen’s Aid Society to advocate on their behalf, and if that’s true, it might account for his being aggressive in his fundraising efforts. But still, not the kind of attitude one might hope for in a Friend. As Jim often says, sometimes the meeting will disappoint you, and sometimes you’ll disappoint the meeting. This strikes me as an instance of the latter.

Greetings

I too am a decendent of Nantucket island families, including the Coffins. The Swains went on island in about 1660, at the same time as the Coffin family. The Swain and Coffin families(Levi Coffin’s grandfather) went off island in about 1773.

I’m decendent of individuals considered radical anti-slavery abolisionist. They believed in immediate, unconditional and uncompensated freedom for enslaved. Slavery was a sin after all. Slaver,

Henry Clay was a major player in the American Colonization Society, and he was no friend to enslaved. There was no making things right, as many slavers lived in fear of their property rising up and causing armed isurection. Slavers wanted freed slaves to be sent away also.

The seeds of the split were sown at the Lost Creek meeting house in Tennessee. At Elihu Swain’s home at Lost Creek Tenn., the first Tennessee manumission society was formed and signed by members, including Charles Osborn . This event is identified in Levi Coffin’s “Remberences”. George Washington Julian congressman from Wayne County Indiana identifies this event in his book. “The Rank of Charles Osborn “. The Swains came to Wayne County, Indiana Aug 8. 1815.

The individuals identified as moderates (the body), purhaps were attempting to curry favor with Henry Clay. Clay scheduled a campaign stop in Richmond Indiana in 1842, which also coincided with Yearly Meeting in Richmond. Anti-slavery friends, including Charles Osborn, were purged or dismissed prior to Henry Clay speech at the Yearly. Imagine a slaver welcomed into the meeting. By this time many Quaker became rich trading and dealing in slave produced product. Friends were not innocent and were complicit in selling enslaved produced product.

A Petition was give to Clay requesting that he release his enslaved. He refused and he went as far as saying, if the Quaker wanted to to free his slaves they needed to pay for them, as they were his property to do with as he pleased. He went on to tell his petitioners – “mind your own business”. It’s said the “Clay incident”, was the reason Clay lost the 1844 election for president.

Charles Osborn was the key figure. In the split When Levi headed for Cincinnati-Charles Osborn went to Cass County Mi. Charles and Hannah Swain Osborn witnessed the 1847 Kentucky raids. Several family cabins harboring freedom seekers were attacted by Slavecatchers. Slavecatchers were associates of Henry Clay.

After the Kentucky raids Osborn returned to Porter County Indiana he’s buried there in a unmarked vandalized grave.