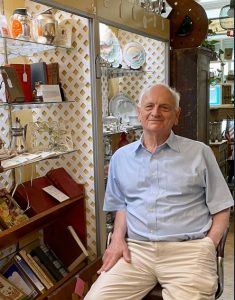

Cincinnati Friends Meeting (CFM) new member Charles “Charlie” Wallner has developed a career philosophy that sounds fairly spiritual.

Cincinnati Friends Meeting (CFM) new member Charles “Charlie” Wallner has developed a career philosophy that sounds fairly spiritual.

As a longtime community organizer, Charles said, “I’m not against a top-down or bottom-up approach to community outreach, but I think you’ve got to have a mesh. No one goes to work in the same town, or goes to church in the same neighborhood, or to school within 100 feet of where they live. Everything exists in a mesh, interconnected in a web.”

“Connecting the fibers that hold people together,” he added, “that’s community.”

Part of what attracted him to the CFM community is “that people are pretty open to their pain. What sold me was when Jim [Newby] gave a message on the prodigal son and I let myself get involved in the discussion.” Charles mentioned the loss of his wife once during worship, “although I left so quickly and Jim said I should have stayed.” He currently attends a spiritual nurture group.

He knew a few Quakers, but was more familiar with the subject of his master’s thesis: Puritans. “I had no grounding in Quakers,” Charles admitted. After attending an Episcopal church, Charles said he was “looking for something more subliminal. One day—people are always looking for the sign that says the church is down the road—I found it, the little sign on Montgomery Road. The timing, just before COVID, was right. Time for me to find a church, and I just kept driving down Keller Road. I was looking for a faith that was a lot more introspective in trying to find out what we are in this world.”

Charles was raised and educated in the Catholic Church in Queens, New York, “attending as a representative for [my] family for most of my youth until my brother, Robert, came along after ten years.” Charles earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at City College of New York. Certified in history and social studies, he taught “everything” in the public school (PS) system, landing at PS 28 and working with third and fourth graders until the “great layoff” of 1976. He found work as a doorman in the building where Nelson Rockefeller’s daughter lived in the penthouse and Robert Redford, on the seventh floor.

He saved his money and moved to Kentucky after visiting a friend and teaching colleague there. As one of the founders of the Woodland Jubilee for folk music, Charles produced a number of successful festivals in Lexington, falling in with musicians, folk dancing, and non-profit work. His brush with the Ritchie family evolved into an interest in music and dance as well as a 1986 festival honoring the Appalachian musicians, when they were recognized by the president, Congress, and the governor of Kentucky.

For nearly 25 years, Charles worked in the field of alcoholism and drug use prevention. First in central Kentucky, he eventually led the Kentucky Alcoholism Council’s Louisville office. “I got on the Baptist circuit almost every Sunday night talking about alcohol, drugs, and kids,” he recalled. “They were such good audiences, sincere and a departure from so much parental denial.”

Charles later tapped into his community organizing skills in Northern Kentucky, again around alcoholism and drug issues. For ten years he was the Community AIDS Coordinator for the Cincinnati AIDS Consortium, overseeing public money for assistance to southwest Ohio.

“I found community work,” Charles said. “Actually, it found me. I have always believed my background in history helped. I deeply believe everybody’s got a story to tell.”

He also pursued family history and learned that his grandparents, great-uncle, and aunt were in vaudeville and on Broadway. One uncle was a recording star for Edison. That background taught him that “family is a network, and a web, connected in time by success, failure, loss, and love.”

Between positions in the chemical dependency profession, Charles moved to Cincinnati to write a grant for the Cincinnati Museum Center’s Ice Age exhibit.

At a contra dance in Cincinnati, Charles met a woman reeling her way in the other direction and asked, “Do you want to dance or perform?” He wrongly assumed that Jane, who would become his wife, was part of the “snooty” dance academy. She wasn’t, just a very good dancer. The next time they met, again at opposite ends of the floor, dance filled in for words as a relationship blossomed.

Charles encountered CFM member Jim Crocker-Lakness, who died last year, a few times while contra dancing. “We never really met, just on the dance floor,” Charles said. Learning that Jim considered dancing spiritually transformative, Charles said it can be: “Depending on where you’re at, dance, like the waltz, can be sensuous, ethereal, or both. For me, it is ethereal. I go to English country dancing every two weeks; sometimes it’s just gorgeous with the music and others, just fun.”

Charles relishes the time he spent with Baptist Minister Rousseau O’Neal II, former head of the Faith Community Alliance (FCA) of Greater Cincinnati. “He would walk into a room, call everyone brother, and level the field,” Charles observed. After the death of Timothy Thomas stoked outrage in 2001, a group of predominantly Black preachers took to the streets to ease tensions. In response, the FCA recruited 2,000 people “who stopped for three minutes to say something nice to someone next to them, just to themselves or to call someone.” Although not well remembered, Charles believes “The Three Minutes of Peace” was important, exhausting, yet rewarding work. It was recognized with proclamations from the mayor of Cincinnati and other communities. O’Neal, Charles said, “went to a lot of places in turmoil, prayed, and got things done.” He cites Sister Alice Gerdeman, then-director of the Cincinnati Intercommunity Justice and Peace Center, as an inspiration.

The FCA, Charles said, was an odd assortment of hospital, labor, religious, alcohol, drug, AIDS, and gun control organizations: “We didn't run anything, but mobilized the community organization web over 20 years.”

There’s that web again, “the indefinable mystery,” as Charles put it. “We’re inspired at moments to know what we have to do and do it with no guarantee of success,” he said. “That’s the bedrock of how life happens. The very fact of the human incapacity to survive proves there’s a God, that we can’t do it on our own.”

Thank you, Charles, for sharing yourself with us.

What a life you’ve led. Given and received. You come across as appreciative, reflective, and quietly joyful. Plus you make me want to get out on the dance floor!