During the nineteenth century, it was impossible for Cincinnati Friends to avoid being drawn into the most contentious debate in the history of our nation: the clash over slavery.

Quakers were universally opposed to slavery by the mid-nineteenth century, but it had been a position arrived at gradually. When visiting Barbados in 1671, George Fox wrote, “I desired [Friends] also that they would cause their overseers to deal mildly and gently with their negroes, and not use cruelty towards them, as the manner of some hath been and is; and that after certain years of servitude they would make them free.” In short, Fox did not insist that all Friends abstain from owning slaves, but encouraged their decent treatment and eventual liberation.

Quakers were universally opposed to slavery by the mid-nineteenth century, but it had been a position arrived at gradually. When visiting Barbados in 1671, George Fox wrote, “I desired [Friends] also that they would cause their overseers to deal mildly and gently with their negroes, and not use cruelty towards them, as the manner of some hath been and is; and that after certain years of servitude they would make them free.” In short, Fox did not insist that all Friends abstain from owning slaves, but encouraged their decent treatment and eventual liberation.

In 1688, Germantown Monthly Meeting in Pennsylvania was the first Quaker meeting in North America to present its yearly meeting with a petition to bear a testimony against slavery. By 1696, Friends were discouraged from participating in the importation of slaves. By 1730, buying slaves that were already in the country was still acceptable, but buying newly imported slaves was not. By 1754, this injunction had been broadened to discourage the purchase of any new slaves, although retaining those that had been previously purchased or inherited was condoned. By 1758, Friends were strongly encouraged to free their slaves. By 1776, continuing to own slaves was grounds for disownment in some yearly meetings.

Since the inception of Cincinnati Friends Meeting in 1815, its members had been regularly responding to the following query in the Discipline:

Are Friends careful to bear testimony against slavery? Do they provide, in a suitable manner, for those under their direction, who have had their freedom secured; and are they instructed in useful learning?

One member of Cincinnati Friends Meeting who took this query particularly to heart was Mordecai Morris White. His family had been Quakers for generations, but continued to own slaves at their North Carolina plantation. In 1846, when White was only 16 years old, he and his younger brother and his step-grandmother inherited a large estate from his maternal grandfather, including a number of slaves. Perhaps his education at the Friends Boarding School in Indiana heightened his discomfort with the situation. By the time he was in his early twenties and settled in Cincinnati, “the matter came to him with a powerful grasp of conscience,” and White decided to take action. While making his annual visit to the family’s property in the South, he began making arrangements to take his slaves to a northern free state:

The first step which Mr. White found necessary was one which required him to take every man, woman, and child to Elizabeth City, the county seat, sixteen miles distant, and before the clerk of the court, to certify ownership. Each slave was here accurately described and placed upon record, the name, shade of color, height, weight, thickness of the lips, etc., etc. This gave him legal permission to take them out of the State which, under the operation of the slave laws then existing, he could not otherwise have done without the interference of officers of the law.

The prejudice against manumission was so strong that he could not induce any white man for any sum offered to aid him in his undertaking.

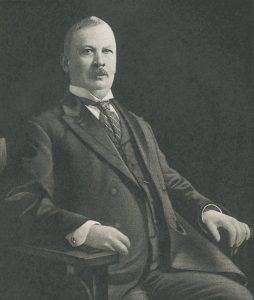

White ended up hiring two carts with mules to transport the belongings of his slaves, who began their journey at three o’clock in the morning to ensure that they avoided any encounters with either local authorities or disapproving neighbors. White rode on horseback; the rest traveled by foot for the 60-mile journey to Norfolk, Virginia, camping in the woods over the course of the next few days. While in Norfolk, White was offered ten thousand dollars in gold for his “gang,” but turned it down. The group then traveled by steamer from Norfolk to Baltimore, and by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad to Wheeling, West Virginia. From there, they took a steamer to Cincinnati, where they remained for a few days before traveling by rail to Raysville, Indiana. White rented and furnished two houses there for his former slaves, and found jobs for the men chopping wood, making fencing rails, and other employment that would allow them to provide for themselves. One of those former slaves, a man named Boston, took White’s last name as his own. Upon his death in 1893, Boston White was buried in the Raysville Friends cemetery.

Those who did not personally own slaves found other ways to bear testimony against slavery. In 1829, Ephraim Morgan resigned his position as a partner at the Liberty Hall & Cincinnati Gazette rather than be associated with a publication that carried advertisements seeking the return of runaway slaves.

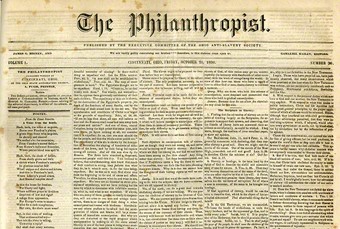

Achilles Pugh, who joined Cincinnati Friends Meeting in 1832, was a printer by profession. In April of 1836, he began publishing The Philanthropist, an abolitionist newspaper edited by James G. Birney for the Anti-Slavery Society of Ohio. In July of that year, a pro-slavery mob broke into the printing house, tore up the paper, poured out the ink, scattered the type, and dismantled the press, throwing parts of it into the Ohio River. The mob even went to Pugh’s home to ensure that no additional printing materials were kept there, but committed no violence. The next day, Pugh went back to his office, literally picked up the pieces, and resuming printing The Philanthropist.

Achilles Pugh, who joined Cincinnati Friends Meeting in 1832, was a printer by profession. In April of 1836, he began publishing The Philanthropist, an abolitionist newspaper edited by James G. Birney for the Anti-Slavery Society of Ohio. In July of that year, a pro-slavery mob broke into the printing house, tore up the paper, poured out the ink, scattered the type, and dismantled the press, throwing parts of it into the Ohio River. The mob even went to Pugh’s home to ensure that no additional printing materials were kept there, but committed no violence. The next day, Pugh went back to his office, literally picked up the pieces, and resuming printing The Philanthropist.

Although Quakers were united in their opposition to slavery, there were nevertheless mixed feelings about how to handle the current enslaved population. Some considered it a matter of individual conscience and thought that people should free their slaves as they became personally convinced to do so. Others, wishing to redress the wrong of removing black people from their native countries, favored colonization—sending the slaves back to Africa as a condition of their freedom. Others believed in abolition—the immediate, unconditional emancipation of all slaves throughout the country.

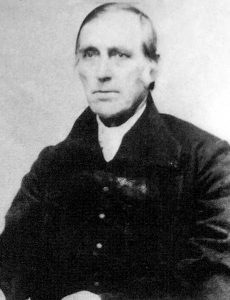

By 1842, this diversity of opinion caused a rift in Indiana Yearly Meeting that lasted for thirteen years. Among those who led the creation of Indiana Yearly Meeting of Anti-Slavery Friends was Levi Coffin, a staunch abolitionist who was at that time living in Newport, Indiana.

Coffin believed that slavery was inherently evil, and that complete emancipation was the only conscionable approach. In addition to disseminating information about the immorality of slavery, Coffin also tried to undermine the economic foundation of the practice by operating a dry goods business that carried no products produced by slave labor. Indeed, it was this experience that brought him to Cincinnati. The supply of free-labor cotton goods and groceries was inadequate in many parts of the country, and in the fall of 1846, a convention of abolitionists met to address the problem. They decided to establish a wholesale repository in Cincinnati, which was then a center of commerce due to its proximity to the Ohio River, and they persuaded Coffin to oversee its operation. Although he was hesitant to leave his home and friends in Indiana, in the spring of 1847 Coffin agreed to go to Cincinnati for five years. Little did he know that he would spend the rest of his life there.

By the time Coffin came to the area, he and his wife Catherine had already been involved for more than twenty years in the “Underground Railroad”—a network of black and white individuals who helped runaway slaves flee to freedom in the northern states and Canada. “We hoped to find in Cincinnati enough active workers to relieve us from further service, but we soon found that we would have more to do than ever,” wrote Coffin. “[Many] white people, who were at heart friendly to the fugitives, were too timid to take hold of the work themselves. They were ready to contribute to the expense of getting the fugitives away to places of safety, but were not willing to risk the penalty of the law or the stigma on their reputation, which would be incurred if they harbored fugitives and were known to aid them.”

Coffin, who had long since accepted such risks, continued his work until the issue was ultimately addressed by an event that transformed the entire country: the Civil War.

This article comes from the book Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to Cincinnati Friends Meeting.