In honor of our meeting's 200th anniversary in 2015, Sabrina Darnowsky wrote a book entitled Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). To help people become more familiar with our past, sections of this book are being posted via the online Traveling Friend. You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to the meeting.

It began simply. Just a few Quaker families, settlers in a frontier town, who as early as 1811 were gathering together in one another’s homes and sitting in silent worship, waiting for the leading of the Spirit. They could not have known that they were starting a community that would touch the lives of people around the world.

Like most of the pioneers in the Northwest Territory, these members of the Religious Society of Friends came from diverse regions: rural Virginia; Nantucket Island in Massachusetts; urban Philadelphia and other parts of Pennsylvania; North and South Carolina; Maryland; New Jersey; and even Tennessee. They likewise came for diverse reasons. Some, forsaking the traditional Quaker commitment to peace, might have been given land grants as payment for their military service during the Revolutionary War. Some, adhering to the peace testimony, might have come after having their property confiscated as punishment for not paying war taxes. Some found it objectionable to live in areas that condoned slavery. Some simply sought more land or greater economic opportunities. For all, it was a chance at a new beginning.

One of those pioneers was Christopher Anthony. Born in 1744 in Virginia (when it was still a British colony), Anthony grew up in a prosperous family on a large plantation that at one time included more than 20 slaves. The religious affiliation of his father, Joseph Anthony, is not known. His mother Elizabeth, however, was from a family with Quaker roots. Her sister, Sarah Clark Lynch, hosted meetings for worship in her home and eventually donated the land for South River Monthly Meeting’s meetinghouse in Virginia.

Although he must have been exposed to Quaker faith and practice from an early age, Christopher Anthony did not join South River Monthly Meeting until he was 24 years old, already married to his first wife, Judith Moorman, and father to two children. Only four months later he was appointed clerk, a position that involved managing the administrative aspects of the Meeting and discerning whether or not there was unity among its members in making decisions. By the time he was 25, he was appointed an Elder, which included the responsibility of providing counsel and encouragement to the Meeting’s ministers. And when he was 33, Anthony himself was recorded as a minister. (Quaker ministers are not ordained and at that time did not have to have any particular religious training. Recording is a form of recognition given to individuals who demonstrate a gift for speaking during worship or performing other pastoral duties.)

Like Friends from centuries past, Anthony felt led to reach out to others beyond his own Meeting. Within a year of being recorded as a minister, he began visiting Quakers in nearby meetings in Virginia. Fewer than six months later, he was given a minute—a letter of introduction and endorsement—to travel in North and South Carolina. In 1804, he “went on [a] missionary trip to [visit] people ‘not of our Society’.” And in 1808, when Anthony was 63, he was granted a minute to travel to Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Ohio, including a stop in Cincinnati.

According to Anthony’s granddaughter, Mary P. Hart, “There were not many Friends in Cincinnati at that time, but those who were here had treated [him] very kindly and extended a great deal of hospitality to him.” Anthony was “so pleased with Cincinnati, its surroundings and its people that he decided to make it his future home. As soon as possible after his return [to Virginia], he sold his place, gathered up his goods and made ready for his removal to this growing city.”

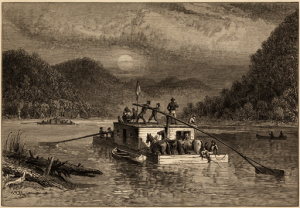

The Anthony family made the first part of the journey through the Appalachian mountains by carriage and horseback. “The household goods came in wagons and with them a family of negroes,” wrote Hart. “The man was a descendant of a slave of grandfather’s before grandfather joined the Society of Friends, at which time he set all his slaves free. Our travelers came in this way to the mouth of the Kanawha; here they took a flat boat and came down the Ohio. They arrived in Cincinnati on one Sunday afternoon and found several Friends who knew of their expected arrival waiting at the wharf for them.”

The Anthony family made the first part of the journey through the Appalachian mountains by carriage and horseback. “The household goods came in wagons and with them a family of negroes,” wrote Hart. “The man was a descendant of a slave of grandfather’s before grandfather joined the Society of Friends, at which time he set all his slaves free. Our travelers came in this way to the mouth of the Kanawha; here they took a flat boat and came down the Ohio. They arrived in Cincinnati on one Sunday afternoon and found several Friends who knew of their expected arrival waiting at the wharf for them.”

Anthony brought with him not only his second wife, Mary Jordan (who had been an Elder and clerk of the women’s meeting at South River Monthly Meeting), but also three of his twelve children: 27-year old Penelope, 22-year-old Rachel, and 20-year-old Charlotte. Anthony’s 32-year-old daughter Hannah and her husband, John Davis, along with their four children, came to Cincinnati about a year later.

By the time Anthony arrived in Cincinnati, he found himself in a situation similar to the one he might have experienced as a youngster, when Quakers gathered for worship in his Aunt Sarah’s house. About 32 families were meeting together in local homes, including those of John F. Stall, Oliver M. Spencer (a Methodist minister), Martha Perry, Cyrus Coffin, and Elizabeth Folger. As the number of Quakers in the area continued to grow, it became clear that they needed more space to worship together than individual homes could provide. It was time to look for a meetinghouse.

To be continued...