George Fox, the founder of the Religious Society of Friends, noted that, in addition to worship, one of the functions of the meeting was to “admonish and exhort such as walked disorderly or carelessly, and not according to Truth.” Quakers approached this task according to the guidelines laid out in Matthew 18:15–17 (King James Version):

Moreover if thy brother shall trespass against thee, go and tell him his fault between thee and him alone: if he shall hear thee, thou hast gained thy brother. But if he will not hear thee, then take with thee one or two more, that in the mouth of two or three witnesses every word may be established. And if he shall neglect to hear them, tell it unto the church: but if he neglect to hear the church, let him be unto thee as an heathen man, and a publican.

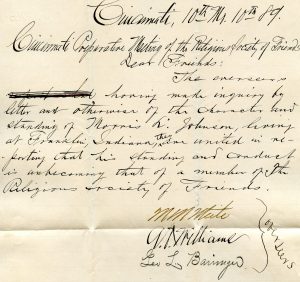

By the early 1700s, the responsibility of “treating with offenders” fell to individuals known as overseers. When Cincinnati Friends Meeting was first established, two men and two women were regularly appointed to this position.

Given the close proximity within which Cincinnati Friends lived and worked, it is possible that the overseers themselves might have observed inappropriate behavior among members of the meeting. In other cases, a member (or even an individual outside the meeting) might have approached the overseers with a complaint. After speaking with the individual privately, the overseers would sometimes find it appropriate to inform the men’s or women’s preparative meeting of breaches of conduct. That meeting would then determine if the matter should be brought up at the monthly meeting. If the individual showed sufficient contrition—acknowledging and condemning the deviation, which was typically done in writing—then no further disciplinary action would be taken. However, if the person expressed no regret, or did not appear to be sincerely repentant, a testimony of disownment would be prepared against that individual.

Unlike excommunication, which in some denominations implies spiritual condemnation, disownment from a Quaker meeting simply meant that one’s membership in that meeting was revoked. Disowned members were not allowed to participate in meetings for business or serve in any positions, although some continued to attend worship. It was recommended that disownment “be done in such a disposition of mind as may convince [the disowned individuals] that we sincerely desire their recovery and restoration,” and any member disowned by a monthly meeting had the right to appeal that decision to the quarterly meeting, and from there to the yearly meeting. If the person later apologized for the offending action, that person could be reinstated by the meeting.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, the leading cause for disownment among Cincinnati Friends was for "outgoing in marriage" (marrying a non-Quaker) or "marrying contrary to Discipline" (which might include having the wedding ceremony performed by a justice of the peace or paid minister). Even the daughter of the meeting's minister, Christopher Anthony, was not exempt from scrutiny. When Charlotte Anthony married Ephraim Morgan in May of 1814, he was not a Quaker, and the ceremony was performed by a Methodist minister. She avoided disownment by apologizing for her action the following August. If there were hard feelings over this, they appear to have dissipated over time, because in 1823, Ephraim Morgan became a member of Cincinnati Friends Meeting. He later acted as a trustee for the meeting’s property, served on numerous committees, donated generously to support the activities of Friends, and eventually became a recorded minister himself.

Disciplinary action was taken for other causes as well. For example, violent behavior was not tolerated at any level. Micajah Terrell Williams was admonished because he “used uncivil language and struck a man.” Mordecai Smith was likewise dealt with for “quarrelling and striking a man.” Although Ohio had no law against dueling, it was contrary to the Quaker peace testimony. Elisha Nicholson, who had just been received from Philadelphia Monthly Meeting the preceding month, was chastised “for being instrumental in giving a challenge for a duel, and attending at the place proposed, with pistols, with intent of violence.”

Participation in military activities was also discouraged. Like other states, Ohio had various militia groups that were expected to defend local residents against attacks, whether from Native Americans, foreign forces, or internal insurrectionists. Although the militias had not been engaged in active duty since the end of the War of 1812, able-bodied men of a certain age were expected to report for periodic drilling. This was referred to as mustering. Individuals who did not participate were charged a fine, and those who did not pay the fine would often have some of their property or possessions seized and sold to pay it. Among Quakers, it was a disownable offense to either participate in the militia or to pay the fine, and the Society did make an effort to reimburse members who suffered losses as a result of those seizures. In 1815, John S. Thomas was disowned because he “attached himself to a military company.” Two years later, Amos Haines was dealt with because he “attended military muster for the purpose of saving a fine.”

Another uniquely Quaker infraction was taking an oath, whether it was done as part of the process of being sworn into a public office or while testifying in court. Scripturally, the basis for this could be found in both Matthew 5:33–37 and James 5:12: “But above all things, my brethren, swear not, neither by heaven, neither by the earth, neither by any other oath: but let your yea by yea, and your nay, nay; lest ye fall into condemnation.” For Quakers, honesty and straightforwardness at all times was a matter of integrity; they did not believe that there should be one standard of truth in private life and a different one in public life. In fact, refusing to swear in court was one of the leading causes of imprisonment for seventeenth-century Quakers. So it was a concern among Cincinnati Friends when Samuel Talbott had to be admonished for “taking an oath.”

Friends were also instructed to avoid other transgressions, including “frequenting stage-plays, horse-races, music, dancing, and other vain sports and amusements; also, in a particular manner, from being concerned in lotteries, wagering, or any kind of gaming; it being abundantly obvious, that those practices have a tendency to alienate the mind from the council of divine wisdom, and to foster those impure dispositions which lead to debauchery and wickedness.” Joining the Free Masons was also discouraged because their “vain and ostentatious processions…are altogether inconsistent with our religious profession.” So it was an issue at the meeting that David Thatcher was “endeavoring to encourage a lottery,” although he was not disowned for the offense. Christopher A. Johnson likewise escaped disownment even though he had “neglected the attendance of our meetings, attended places of diversion and been dancing.” Both Josiah Haines and Davis Embree were disciplined for joining the Free Masons.

Some indiscretions discussed in monthly meetings were of an extremely personal nature. For example, Job Pugh married Sarah Martin in August of 1818, but more than a year later, he was “treated with for unchaste freedom before marriage with her who is now his wife.”

Quakers were also particularly concerned about the use of “spirituous liquors.” Friends at the time were not satisfied to simply discourage imbibing among the members of their own Society; they perceived this as a social ill that needed to be combated on a wider scale. “Is it not affectingly to be observed,” inquired the Discipline, “that a baneful excess in drinking spirituous liquors is prevalent amongst many of the inhabitants of our land? How evident are the corrupting, debasing, and ruinous effects…to the impoverishment of many, distempering the constitutions and understandings of many more, and increasing vice and dissoluteness in the land...” It was therefore not enough to simply prohibit Friends from drinking liquor (except for medicinal use). They were also not allowed to “sell or grind grain for distillation, or furnish fruit or other materials for that purpose; and also such as aid the business by furnishing vessels to prepare or hold such liquors, or are concerned in conveying it to or from market, or vend, or in any wise aid the commerce of that article.” So although Amos Haines was chastised because he “made too common use of spirituous liquors,” Oliver Martin was equally reprimanded for “being concerned in distilling and vending spirituous liquors.”

The Society was concerned not only with the moral actions of its members, but with personal financial activities as well. “We do not condemn industry; we believe it to be not only praiseworthy, but indispensable,” explained the Discipline; “it is the desire of great things, and from the engrossment of the time and attention, from which we desire that our dear Friends may be preserved.” To further that purpose, and to ensure that the reputation of the Society was not adversely affected by improper fiscal conduct on the part of its adherents, the Discipline advised Friends to “be careful not to venture upon business they do not understand, nor launch into trade beyond their abilities, and at the risk of others—but that they bound their engagements by their means: and when they enter into contracts, or agreements, whether written or by words, that they endeavor on all occasions strictly to fulfill them.” When the meeting had reason to fear that a member was in financial trouble, it was incumbent upon the meeting to intervene, either providing the individual with advice or even acting as an arbitrator between that person and his creditors. Of course, such intervention was not always welcome. The men’s meeting minutes noted that “Samuel Talbott left this place suddenly while under dealing for neglecting payment of a just debt, and under circumstances unfavorable to his reputation.” They were apparently able to work things out, however, since Talbott was not disowned over the incident.

This article comes from the book Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to Cincinnati Friends Meeting.

Thanks Sabrina. This all seems “quaint” now. How is it relevant to our current situation?

These CFM Roots posts are intended to share information about our meeting’s past and provide opportunities to reflect on how and why we might do things differently today. Our current practice of Eldering grew from what were once official roles, although obviously the focus is no longer on personal behavior outside the faith community. (For a Society that was so sensitive to the use of pagan names for days of the week and months of the year, you’d think we would have come up with a better term than “overseer” with all of its slavery-related implications, although it might have originated from Acts 20:28–“Take heed therefore unto yourselves, and to all the flock, over the which the Holy Ghost hath made you overseers, to feed the church of God, which he hath purchased with his own blood.”)

Even today, I think we can take good lessons away from some of these former practices: discussing an issue one-on-one before involving others. Approaching concerns about a person’s behavior with love and the hope of restoring unity within the community. Recognizing that how we live in the world reflects our spiritual condition.

Thanks Sabrina. “Taking lessons away from former practices” is itself good practice, and the examples you give are all well taken. Discussing an issue one-on-one before involving others sometimes requires real discipline!