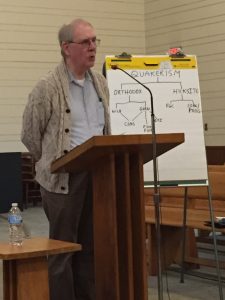

Earlham College Professor of History and author Tom Hamm spent a day with us in October for a seminar on on Quakers in America, focusing largely on the tremendous changes that took place in the Religious Society of Friends during the nineteenth century.

Earlham College Professor of History and author Tom Hamm spent a day with us in October for a seminar on on Quakers in America, focusing largely on the tremendous changes that took place in the Religious Society of Friends during the nineteenth century.

Those changes began in the late 1820s, when five yearly meetings split into two factions. One group sympathized with the Quaker minister Elias Hicks, who emphasized reliance on the Inner Light over the authority of scripture, regarded Jesus as more human than divine, and questioned whether a blood atonement was even necessary for the forgiveness of sins. The other group, who held a more conventionally Protestant understanding of their faith, called themselves the Orthodox. Here in Cincinnati, the division between the Hicksites and the Orthodox was so bitter that Friends built two separate meetinghouses on the same parcel of land on Fifth Street. (The Hicksite meeting was laid down late in the nineteenth century; our meeting descended from the Orthodox branch.)

The next schism among the Orthodox was between those who embraced the teachings of Joseph John Gurney and those who preferred the views of John Wilbur. Gurney was a charismatic English Quaker who encouraged Friends to study the Bible and engage more closely with other Christian denominations. Wilbur thought Gurney was straying too far from the unique characteristics of Quakerism, and a number of Friends rallied to his side. This split had less effect on Cincinnati Friends, who were solidly in the Gurneyite camp.

Working with other denominations on issues such as abolition further brought down the “hedge” that had long shielded Friends from non-Quaker influences. In the last half of the nineteenth century, some meetings began embracing the holiness movement, which emphasized instantaneous salvation and sanctification rather than a gradual process of spiritual growth. In the course of a few decades, meetings that had once practiced silent worship with occasional vocal ministry were introducing revival meetings, singing, altar calls, and paid ministers. Some went so far as to repudiate the very concept of an Inner Light.

Even some of Gurney’s followers found these changes too drastic. A group of them reunited with the Wilburites to form what we today call Conservative Friends, some of whom still observe such customs as plain dress and speech. And when a number of Quakers began opposing the extremes of the holiness movement, those who felt led to support many of its positions split off to form the Evangelical Friends Church.

If nothing else, all these schisms demonstrate that we are a people who continually reflect on our beliefs and practices. We seek to find the appropriate balance between the authority of scripture and the leadings of the Spirit, between adhering to principles that set us apart and the influence of the larger culture. It is a journey that we make every day, and will hopefully continue to make in the centuries to come.