In the nineteenth century, many Cincinnati Friends felt called to address the needs of the city’s most vulnerable citizens: its children. Some had mothers who had been imprisoned and had no other option but to take their children to jail with them or leave them homeless. Some youngsters were under the care of single parents who had to leave them alone all day while they worked. Some children came from homes devastated by alcoholism or other chronic problems. Without strong families or supportive communities, many of these children were left to wander the streets, sometimes resorting to begging and petty thievery.

In 1860 Murray Shipley and a few other Cincinnati Friends sought to alleviate some of these problems by starting a Sabbath school in a basement room on Mill Street on the west side of town. They called their undertaking Penn Mission in honor of William Penn, the Quaker governor of the Pennsylvania Colony. Over the years, the work of the Penn Mission Sabbath School had a marked effect; even the local police noted its reforming influence on the rough character of the neighborhood.

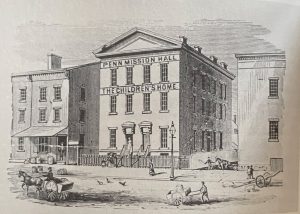

However, the Mill Street facility could accommodate only about seventy pupils. In March 1863 Murray paid $2,500 of his own money (more than $60,000 in 2024 dollars) to purchase land and initiate construction of a three-story brick building to provide a permanent home for the Penn Mission Sabbath School.

In early 1864 a group of three Quaker women—Murray's wife Hannah, Margaretta S. Hinchman, and Hannah P. Smith—took the additional step of opening a day school in the Penn Mission building, offering an education and warm meal to impoverished youngsters whose families could not afford the clothing and supplies necessary to attend the public schools.

Yet for Murray's mother-in-law, Mary J. Taylor, a day school alone was not a sufficient response to the needs of the children in the area. At her prompting, the three-woman committee expanded its membership and soon began providing lodging to homeless children who had nowhere else to go. The Children’s Home was incorporated in December 1864, with Murray as the president of the Board of Trustees.

Many other Quakers were involved in The Children’s Home as well. Dr. William H. Taylor donated his medical services there, and also served as a trustee from 1884 until his death in 1910. Daniel Hill, who was then a minister at Cincinnati Friends Meeting, was the first superintendent of The Children’s Home. Its second was another Friend, William Haydock. He and his wife Emma also operated the 75-acre farm northeast of College Hill, where older boys could be sent “to separate them from the evil influences of the city and old associations; and to prepare them for farm duties and accustom them to the exchange of a life of vagrant independence for one of industry and order.”

Indeed, it was a common belief at the time that life in the country offered a more wholesome environment. Unlike many other nineteenth-century institutions that too often became “home” to their wards, The Children’s Home endeavored to quickly place children in suitable families, preferably rural ones, and the interconnectedness of the Quaker community helped facilitate that. Groups of children were sometimes taken to quarterly meetings in Indiana and southwestern Ohio so that they could find homes with Friends, and local committees were formed to ensure that the children were properly cared for. Between 1864 and 1876, about 452 boys and 342 girls were placed with families by The Children’s Home.

Murray and Hannah Shipley’s son, Caleb, later served on the Board of Trustees himself. In 1910, his was one of the first voices recommending that The Children’s Home hire black staff members and provide day care services to working black women. This progressive idea was rejected by the superintendent at the time, but two years later The Children’s Home began working with the Juvenile Court to place a few black children for adoption. By 1923 The Children's Home was actively working with other organizations such as the New Orphan Asylum for Colored Youth, the Home for Colored Girls, and the Shelter Home for Colored Children to locate foster homes for black youngsters.

As time passed, and The Children’s Home relied less on volunteers and more on professional staff members, the involvement of Cincinnati Friends diminished. However, they had a significant impact on the culture of the organization. “Love and kindness is the law by which the children are governed,” reported one of the women who looked after the youngsters, “and we find it a mightier influence than fear."

In 2022, The Children's Home merged with the St. Aloysius Orphanage to become Best Point Education & Behavioral Health.

Portions of this article are extracted from the book Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to Cincinnati Friends Meeting.