We are not for Names, nor Men, nor Titles of Government, nor are we for this Party, nor against the other, because of its Name and Pretense; but we are for Justice and Mercy, and Truth and Peace, and true Freedom, that these may be exalted in our Nation.

~ Edward Burrough, 1634-1663

Seventeenth-century English Quakers like Edward Burrough were not interested in making political statements; they were interested in making religious statements, some of which had political consequences. King Charles II didn't particularly care that Friends dressed plainly in muted colors in order to demonstrate the importance of simplicity and humility. It made no difference to him that they chose not to honor pagan gods and goddesses by avoiding the common names of the days of the week or months of the year, but rather referred to them as First Day, Second Month, and so on. However, the king and others of high social status did care when Friends demonstrated their belief in the equality of all people by using thee and thou with everyone rather than by using you when addressing their supposed superiors—Your Highness, Your Honor, Your Grace. Those who expected their due deference were incensed by Quakers who refused to remove their hats or to bow or curtsy in their presence.

King Charles was likewise displeased when Quakers refused to pay compulsory tithes to the Church of England because they felt that contributing to the official state religious institution was not required to be in right relationship with God. They chose not to observe the church's calendar of feasting and fasting because they believed every day was a holy day, and they kept their businesses open when others were closed in obedience to church edicts. Friends similarly refused to take oaths of loyalty to the crown because they believed in the scriptural admonition that they should never swear, but rather let their yes be yes and their no be no. And of course, they refused to take up arms, embracing instead the idea that people should beat their swords into plowshares and live together in peace. For these religious statements, lived out in their day-to-day lives, Quakers were often pilloried or imprisoned. It was not until the 1680s, with the Declaration of Indulgence and the Toleration Act, that Friends were finally free to follow their religious convictions without political persecution.

King Charles was likewise displeased when Quakers refused to pay compulsory tithes to the Church of England because they felt that contributing to the official state religious institution was not required to be in right relationship with God. They chose not to observe the church's calendar of feasting and fasting because they believed every day was a holy day, and they kept their businesses open when others were closed in obedience to church edicts. Friends similarly refused to take oaths of loyalty to the crown because they believed in the scriptural admonition that they should never swear, but rather let their yes be yes and their no be no. And of course, they refused to take up arms, embracing instead the idea that people should beat their swords into plowshares and live together in peace. For these religious statements, lived out in their day-to-day lives, Quakers were often pilloried or imprisoned. It was not until the 1680s, with the Declaration of Indulgence and the Toleration Act, that Friends were finally free to follow their religious convictions without political persecution.

Yet because they had a vision of a world that looked more like God's kingdom here on Earth, some Friends imagined what it might be like to have a government that reflected their religious ideals. When William Penn was granted the land that eventually became the state of Pennsylvania (and paid the Native Americans who lived there for it), he decided to conduct a "holy experiment"—establishing a government that offered its citizens not only the freedom to practice their faith (whatever it might be), but also a degree of voice in their government that was unprecedented. The Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges adopted in 1701 expressed many of the principles that would later become the foundation for the United Stated Bill of Rights.

Unfortunately, democracy was sometimes at odds with Quaker testimonies. Friends were still in the majority in the Pennsylvania Assembly when the French and Indian War broke out in 1754. At issue was the ongoing expansion of settlements west of the Blue Ridge mountains that were infringing on Native American territories. Many in the Assembly supported the settlers, and even Friends were divided amongst themselves. As a result, some Quakers withdrew from the Assembly and public affairs in general. Because of their commitment to pacifism, Quakers lost their gubernatorial majority in the election of 1756.

By the time Cincinnati Monthly Meeting was established in 1815, Quakers were decidedly skeptical about any direct involvement in government, viewing it as a source of contention. In 1819, Ohio Yearly Meeting expressed this advice to the members of its constituent Meetings:

...[We] exhort all in profession with us to decline accepting any office or station in civil government, the duties of which are inconsistent with our religious principles...

It is also our judgment that Friends ought not, in any wise, to be active or accessory in electing, or promoting to be elected, their brethren or others to such offices or stations in civil government, the execution whereof tends to lay waste our Christian testimony, or subject their brethren or others to sufferings on account of their conscientious scruples.

If Quakers in the 19th century were wary of wielding the levers of power in government themselves, they were nevertheless not shy about trying to influence those who did. Isaac and Sarah Harvey, who owned a farm near Wilmington, Ohio, personally met with Abraham Lincoln in the early 1860s to implore him to end slavery in the country. Susan B. Anthony, born into a Quaker family committed to social equality, was a vocal advocate for securing women's right to vote. Even here in Cincinnati, Friends implored elected officials to deal justly with those who peacefully protested at local saloons in an effort to promote Temperance laws.

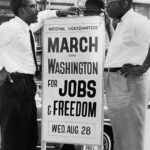

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Friends have pursued all of these approaches to political engagement. Some, like their 17th-century forefathers, choose to make personal religious statements by being conscientious objectors during wartime or by refusing to pay that portion of their taxes that would go toward the military. Others, like their brethren in colonial Pennsylvania, choose to become directly involved in politics, with two Quakers (Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon) even becoming president. Still others, like their 19th-century counterparts, take the path of persuasion, supporting the Friends Committee on National Legislation or marching for equal rights like the African American Quaker Bayard Rustin.

The current book of Faith and Practice published by Wilmington Yearly Meeting summarizes it this way:

Friends regard the state as a social instrument to be used for the cooperative promotion of the common welfare. The source of its authority and the most reliable guide in its administration should be the inward convictions of right possessed by its citizens. "Our highest allegiance as Christians is not to the state but to the kingdom of God. But this does not mean that we have not duties, as Christians, toward the state and the nation to which we belong, or that our attitude toward the state should be a negative one, or one of indifference." (London Yearly Meeting, 1925). Good government depends on observance of the laws of God by those in authority. It behooves all Friends to fit themselves for efficient public service and to be faithful to their performance of duty as they are gifted and guided by the inspiration of God.

May we ever be for justice, mercy, truth, peace, and freedom!

Thanks Sabrina. Your essay is challenging and thoughtful. There are times when I feel “decidedly skeptical about any direct involvement in government, viewing it as a source of contention.” Knowing that you and Alan have chosen the route of direct involvement is inspiring!

Thank you for this excellent and timely piece, joining the past to the present.