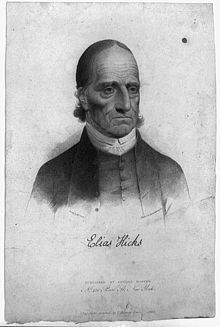

Not long after Cincinnati Friends Meeting was established in 1815, an itinerant Long Island preacher named Elias Hicks became a nexus of controversy among Quakers on the East Coast. In the tradition of George Fox, Hicks strongly advocated for relying on the Inner Light for guidance, to the extent that some Friends felt that he was disparaging the Bible. Hicks was also skeptical of the concept of the Trinity, the virgin birth, and other miracles, leading to accusations that he was a Unitarian and a deist. He also emphasized the human nature of the historical Jesus, and questioned whether a blood sacrifice was necessary for the forgiveness of sins. On a less theological note—but perhaps a more threatening one—Hicks was also concerned that wealth and social status had corrupted many leading Friends, particularly in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, and he was blunt in saying so.

Not long after Cincinnati Friends Meeting was established in 1815, an itinerant Long Island preacher named Elias Hicks became a nexus of controversy among Quakers on the East Coast. In the tradition of George Fox, Hicks strongly advocated for relying on the Inner Light for guidance, to the extent that some Friends felt that he was disparaging the Bible. Hicks was also skeptical of the concept of the Trinity, the virgin birth, and other miracles, leading to accusations that he was a Unitarian and a deist. He also emphasized the human nature of the historical Jesus, and questioned whether a blood sacrifice was necessary for the forgiveness of sins. On a less theological note—but perhaps a more threatening one—Hicks was also concerned that wealth and social status had corrupted many leading Friends, particularly in Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, and he was blunt in saying so.

Hicks’ messages forced Friends to take sides on a difficult question: who has the authority to decide what an individual may believe and say during worship? Who represents the “true” Society of Friends? By 1827, supporters of Hicks within Philadelphia Yearly Meeting had formed their own yearly meeting, and by 1828, Indiana Yearly Meeting (the yearly meeting to which Cincinnati Friends Meeting then belonged) had also split. Those who opposed the teachings of Hicks came to be called Orthodox; those who favored him (or simply opposed the extent to which he was condemned) were called Hicksite. Monthly meetings that leaned predominantly one way or the other were able to align themselves with a particular yearly meeting without deep divisiveness or bitterness. Meetings that were more evenly split—including Cincinnati Friends Meeting—were not so fortunate.

Hicks himself attended a meeting for worship in Cincinnati in October of 1828. When he rose to speak, John Davis asked him to take his seat. Hicks hesitated a moment and then, after thanking the Founding Fathers for declaring that all men are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights (including life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness), he proceeded to preach. Afterwards, Benjamin Hopkins announced that Hicks would hold a public meeting at the courthouse at 3:00 P.M. The event was well attended by many lawyers, doctors, and other professional men, who generally found Hicks' message satisfactory.

On Christmas Day of that year, the first sign of disunity appeared in the men's monthly meeting minutes. The clerk, John Shaw, found himself sympathetic to the Hicksite perspective and refused to read a letter from the Orthodox quarterly meeting, causing the meeting for business to grind to a halt. The Orthodox acted swiftly, stripping Shaw of his clerkship and appointing William Crossman as clerk instead. Crossman and Davis were also appointed to demand that Shaw turn over all existing meeting minutes and other papers. It would prove to be a fruitless quest; the Orthodox were not able to obtain a copy of the meeting’s early records until 65 years later, when they were given a typewritten transcript.

There was growing dissent in the women’s business meeting as well. In January of 1829, the women Friends opted to release Ann Tucker as their clerk, accusing her of insubordination to the Orthodox yearly meeting, promoting Hicksite publications, and illegitimately retaining the women's minutes and papers. Mary Sanders was appointed as clerk in her stead.

Although Tucker and her supporters initially walked out of the women’s meeting, the Hicksites soon came to the conclusion that they had as much right to use the meetinghouse—which many of them had helped purchase—as the Orthodox. The following February, Thomas Shreve and John Pennington were both being being admonished by the Orthodox for violating "good order," but they nevertheless continued to attend meetings for business. When they were asked to leave so that the meeting might be limited to members in good standing, they declined to comply, and the clerk was instructed to note their “intrusion” in the minutes. Indeed, when a committee of Orthodox Friends tried to visit Shreve “on account of his deviation,” he refused to receive them, and he “frequently interrupted [the] meeting by preaching.”

By April, Shreve and Pennington had been disowned, but they continued to attend meetings for business, and the list of “intruders” continued to grow. By May, it included John Shaw (who had already been stripped of his clerkship), Benjamin Hopkins (a former clerk and trustee), William Butler, Jozabad Lodge, William Staunton, John Cadwallader, Hugh Wilson, James B. Johnson, and John Haines. Former members of the meeting who had transferred elsewhere and individuals from other meetings who were sympathetic to the Hicksites periodically attended as well.

With so many contending voices present, the meetings for business descended into chaos. Shaw and Crossman both attempted to clerk the meetings simultaneously, each continually interrupting the other. Ultimately, the Orthodox declared that in participating in meetings for business, the Hicksites were violating the Orthodox’s constitutional right to freedom of religion.

This article comes from the book Friends Past and Present: The Bicentennial History of Cincinnati Friends Meeting (1815–2015). You can obtain a copy of the printed book or a Kindle version from Amazon.com. The proceeds of all sales go to Cincinnati Friends Meeting.